December 23, 2011, - 4:13 pm

Chanukah World War II: Moving Stories of Jewish Soldiers’ Celebrations

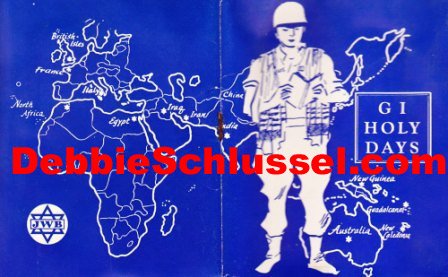

Tonight, at sundown, the fourth day of the Jewish holiday of Chanukah will begin. On Tuesday morning, I showed you some photos of Jewish combat unit soldiers in the South Pacific lighting their menorah. Now, I share with you some touching stories of how our fighting Jewish-American soldiers in World War II celebrated the holiday on the battlefield. Below are those stories, from “GI Holy Days: Jewish Holidays and Festival Observances Among the Armed Forces Thoughout the World,” a miniature book published in 1944 by the Jewish Welfare Board. The Jewish Welfare Board was an organization made up of major Jewish organizations who provided social halls, postcards, games, shaving kits, food, and respite for all of America’s soldiers, Gentile and Jew, both in the States and overseas beginning in World War I and stretching through the 1970s, when the organization disbanded.

The Jewish Marines had come back from the capture of Tarawa. They were encamped on an island in the Central Pacific, on a ridge 3,000 feet above sea level, tough, seasoned fighters, who had lived with death, and yet had not forgotten how to cherish the gentle things that belong to home.

Chaplain Jacob Philip Rudin had traveled the torturous, corkscrew “little Burma Road,” to their mountain encampment to celebrate with them the festival that honors another group of valiant warriors against tyranny–the Maccabees. The chapel was a tent, sides rolled up, open to whistling mountain winds. The pulpit was a homemade table, covered with a blanket. There were no chairs. The men stood around in semi-circle. There were no electric lights. It was necessary to hold Hanukah services early, be finished before the sun went down.

Chaplain Rudin filled the menorah with the little orange candles, so that the barren pulpit would look less bleak. He lighted the Shammas [DS: the candle with which we light the others on the menorah; usually it is elevated above the rest] and the single candle for the first night of Hanukah. The men recited the blessings, sang “Rock of Ages” [DS: the Hebrew song, “Maoz Tzur,” about G-d, which we typically sing after lighting the Chanukah candles each night]. The Jewish Welfare Board’s Hanukah gifts were distributed.

The service and the daylight came to an end together. The Shammas and the single candle burned bravely against the encroaching night. “Then,” Chaplain Rudin wrote, “a lovely and unexpected thing happened. As we stood there in the semi-gloom and I was finishing my talk, the wind blew through the tent and it set the flame flickering from side to side in the closely set rank of candles. And while we watched, the entire menorah was ablaze. I let it burn. It was as though we were sharing together all the eight days of the festival in one sudden, miraculous moment.

“It was night now but atop that distant mountain and in the midst of war, all the lights of Hanukah gleamed through the darkness and made it bright with their golden message of courage and faith and hope.”

On Hanukah, the Jew is fully prepared to believe in miracles. He retells the story of the tiny vessel of oil which burned eight days and assures himself that when a man has faith anything can happen–even Hanukah Latkes in the jungle. When Chaplain David Seligson visited with the soldiers at isolated outposts in Assam, he found their memories of the traditional observance were poignant. His box of JWB [DS: Jewish Welfare Board] religious supplies contained the candles and menorah, but holiday “latkes” [DS: potato pancakes traditionally eaten on Chanukah] were only a fond dream. The makings were non-existent. Who had ever seen fresh eggs in the jungle?

Suddenly, the miracles began to happen. A new unit moved into the area, bringing a Jewish mess sergeant who had in civilian life made knishes [DS: a stuffed (usually stuffed with potatoes) savory pastry eaten by Jews] and latkes. He furnished willingness and a recipe. The Chaplain went out to find the ingredients.

Investigation revealed that in the villages of the Naga hillman, chickens had been seen. These naked head-hunters had been known from time to time to bring eggs into the native bazaars. Chaplain Seligson changed his paper rupees into silver and haggled with the head-hunters. Volunteers, for once pleased to do K.P., began to peel endless sacks of potatoes. Mess Sergeant Levine brought his aides, McAllister and McCoy, and mass production of G.I. latkes commenced.

Elsewhere in India, 250 men gathered in a huge circus tent on the lawn of the home of one of the native Indian Bene Israel [India’s native Jewish community] and each of the candles was lighted by a soldier who had some special reason for rejoicing–paternity back in the States, promotion, or preservation from danger. The eighth candle was lighted by a British soldier of the King’s Brigade, survivor of battle in the Burmese jungles. At services at Jorhat, a Hanukah gift was presented to Chaplain Williams, a Christian Chaplain, in gratitude for his cooperation with the Jewish personnel.

Officers and soldiers stationed near London decided to reverse the familiar procedure of accepting the holiday hospitality of the local community and to act as hosts themselves. As their guests for a Hanukah party they chose120 Jewish orphans who had lost their parents in the blitz of London’s East End, and held their party at the orphanage. Chaplain Judah Nadich told the story of the festival and led the singing of Hanukah songs. Mickey Mouse films were shown and gifts distributed. The dolls and the boxes of clothing sent to the Chaplain by a women’s organization in the United States, were gratefully received, but most welcome were special gifts donated by the service men themselves–candy, cookies, chewing gum–rare and almost priceless delicacies, saved by the men from their rations and packages from home, and presented as Hanukah Zedakah [DS: “zedakah” is Hebrew for “charity”].

In the evening, impressive services were held at the Bevis Marks Synagogue, in London, the oldest synagogue in the English-speaking world in a structure built in 1701 for a congregation established in 1656. Jewish soldiers of the American forces joined with their allies from Britain, Canada, France, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Holland, heard Chaplains of the United Nations conduct the festival service with the choir of the Great Synagogue.

To this stirring religious military service, there is vivid contrast in the celebration which Chaplain Edward T. Sandrow reported from Alaska. The Arctic weather is bitter, the Arctic night long and inky black. Across the ice, the heavy boots of scores of soldiers crunched–men in parkas, mukluks, fur hats, phantom hats, man-borne fortresses against snow and sleet. They crowded the warm, lighted mess hall whose windows were blacked out by the thick rime of heat within and frost outside. Tables were set. Volunteer army cooks (a medical corps lieutenant and several enlisted men) dished up “latkes and gefilte fish.”

“All activity is temporarily halted as we light the Hanukah lights,” the Chaplain wrote. “A mood of seriousness, of historical reflection pervades the atmosphere. For a moment we forget our war. We are transplanted in time and space to Judea. We praise G-d for a military and spiritual victory which in its time brought surcease to Jewish pain. We sing Maoz Tzur (“Rock of Ages”), Mi Y’Mallel [DS: “Who Can Retell?” a Chanukah song]. There is hope in the air. There are dreams of victories to come, of a return to home and loved ones, of happiness in all its potential richness.

“Then a babel of sounds bursts forth, shrieks, laughter. The gefilte fish and G.I. latkes are on the table. They are rapidly consumed. More songs follow. Then instrumental music by a Captain and a Corporal. The Hanukah lights themselves seem to dance. We play “dreidel” [DS: a spinning top game played on Chanukah] and for small stakes. The dredlach [DS: Yiddish plural for dreidel] themselves are works of art. The candles sweat and droop and play along with us. Reluctantly, the evening came to a close. Self appointed K.P.’s begin the job of cleaning the mess hall. We sing “America” and “Hatikvah” [DS: The Hope, the Jewish anthem]. The men start filing out. They are well fortified against cold and darkness. In the midst of war, they have celebrated Hanukah 5704 [DS: the Jewish year]-1943, linked to a deathless, vibrant way of life.”

To all of my Jewish readers, I wish you a continued Happy Chanukah. I’ll be writing a little more about Chanukah before the holiday ends. Stay tuned.

Tags: Alaska, Bene Israel, Burma, Central Pacific, Channukah, Chanukah, Chanukah candles, Chanukkah, Chaplain David Seligson, Chaplain Edward T. Sandrow, Chaplain Jacob Philip Rudin, Chaplain Judah Nadich, David Seligson, Edward T. Sandrow, G.I. latkes, gefilte fish, GI Holy Days, GI Holy Days: Jewish Holidays and Festival Observances Among the Armed Forces Thoughout the World, Hannukah, Hanukah, Hanukkah, India, Jacob Philip Rudin, Jewish Marines, Jewish Welfare Board, Jorhat, Judah Nadich, King's Brigade, latkes, little Burma road, Maccabees, Maoz Tzur, McAllister, McCoy, menorah, Mess Sergeant Levine, Mi Y'Malel, Mi Y'Mallel, Rock of Ages, Shammas, Who can retell?, World War 2, World War II, Zedakah

Debbie, happy Chanukah, I wish you and you’re family and relative memebers to enjoy the holiday, etc.

“A nation is defined by its borders, language & culture!”

Sean R. on December 23, 2011 at 7:28 pm